The Old Testament is simultaneously a historical preparation for and a figurative portrait of God’s New Testament economy. As in a late medieval cathedral, it is the elaborate panel painting behind the altar to which the NT is the caption (see the Ghent Altarpiece). As such, in reading the OT we are often overwhelmed by a level of detail and a pitch of poignant impression that are unavailable in the NT. Witness Lee once remarked, “If we had only the New Testament and not the Old Testament with all its types, we could not see Christ in such a detailed and fine portrait.”[1] The Pentateuch is especially dense with typology. In his first homily on the book of Numbers, Origen said that it was filled with “indications of immense and splendid mysteries.” [2]

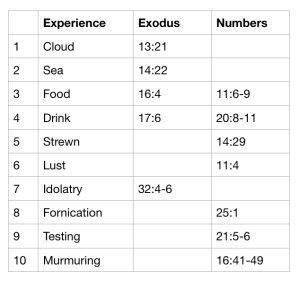

The apostle Paul pioneered the allegorical approach to the OT when he said, “Now these things happened to them as types and they were written for our admonition” (1 Cor. 10:11). “These things” refers to various experiences within the story of the nation of Israel’s origins. Paul then references 10 experiences from Exodus and Numbers, all of them wilderness experiences.

This means that Paul takes the wilderness journey as a type of our Christian life. Our Christian experience began in Egypt with redemption and will conclude in Canaan with the kingdom, but the majority of it is a wilderness journey. This story is what the book of Numbers is all about.

These are the journeys of the children of Israel. –Numbers 33:1

Stories are a powerful medium of truth that move us in a way doctrines can’t. This is a huge reason why we still need to read the OT.

Hans Küng put it well when he said,

As if being stirred could ever be replaced by intellectual comprehension… An apparently vague image or simple narrative may be able to say more of what is ultimately ineffable and lay bare more of the depth structure of reality than the apparently so precise and for that very reason so fixed, inflexible, restricted concept, than the supposedly clear and definite and for that very reason so one-sided and colorless argumentation or documentation. Just so does poetry occasionally come closer to the mystery of nature and of man than the most accurate description or photograph.[3]

The Dangers of the Journey

The Christian life is a journey. For the most part, modern travel has rendered us naive to the dangers inherent in a journey. We pretty much expect things to go smoothly. But journeys are fraught with peril. All the famous journeys throughout history drive this point home—Lewis and Clark, Shackelton, the Odyssey, the Hobbit, Pilgrim’s Progress. A journey is the process of traveling a considerable distance on an arduous course to a particular destination. A journey requires preparation, provision, and perseverance. If you walk from your living room to the kitchen you don’t say, “I’ve been on a journey.” Unless you are melodramatic. You’ve moved, but you haven’t journeyed.

The Christian life is a journey through a wilderness, and the biblical descriptions of the wilderness belie our modern confidence.

The Great and Awesome Wilderness

At the end of his 40 year journey, Moses recounts the story to a second generation, saying, “We set out from Horeb, and we went through all that great and awesome wilderness” (Deut. 1:19). I imagine him saying this standing at the threshold of the promised land; he sweeps his arm back to the “howling desert waste” (Deut. 32:10) behind him and turns his head to cast at it one last retrospective glance.

The wilderness is “great and awesome.” Moses isn’t using informal slang here. These adjectives don’t carry the happy-go-lucky positivity that a 13 year old might give to them. Other translations bring out Moses’ intended sense: “vast and terrible” (DRA) or “immense and forbidding” (NET) or “wide and awful” (Moffatt).

The fact that Moses inserts any adjectives at all here is significant. Robert Alter says that “narrative report in the Bible is famously laconic.” Concise and unadorned. In other words, the Bible doesn’t read like a novel, with juicy descriptions, colorful detail, and analysis of the characters’ psychological states. Even one of the most engaging stories, the story of David in 1 and 2 Samuel is tersely told (Geraldine Brooks has rendered it in vivid hues with her imaginative expansion, The Secret Chord). The stories are stripped down to their essentials—they went here and did this. So for biblical stories this little flare of description is significant. Alter suggests that Moses is making a point—”emotionally, the wilderness is a place to be remembered with fear and trembling, a place that tried the soul of the nation… and the deictic ‘that’ serves to keep it at arm’s length as a haunting memory of a very palpable experience recently undergone.”[4]

Quantitatively

Quantitatively, the wilderness was vast and sprawling. It was something that could swallow up an entire nation, the ancient equivalent of a black hole. It was the place to which, once a year on the goat for Azazel, the entire nation sent their sin away to disappear into “the realm of disorder and raw formlessness… the primordial realm of ‘welter and waste’ before the delineated world came into being.” [5] In the wilderness we bow before forces much greater than us and recognize the limitations of our nature.

Qualitatively

Qualitatively, the wilderness was awe inspiring. Awe is “a feeling of respect or reverence mixed with dread and wonder, often inspired by something majestic or powerful.”[6] The wilderness is something you don’t mess with. Encountering the granite gashes and bare mountains of the southern Sinai, Alain de Botton said, “Beside all these, man seems merely dust postponed.”[7]

Our modern journeys are undertaken with lots of accommodation. We have paved roads and gasoline powered engines, street lights and AC. Convenient stores and restaurants dot the way, while Google maps and iPhones guarantee we will never loose our way or loose our connection. So there’s not much to fear. Our greatest concern on modern journeys seems to be how to stay entertained. Proust hinted at this when he wrote, “Sunrise is a necessary concomitant of long railway journeys, like hard-boiled eggs, illustrated papers, packs of cards, rivers upon which boats strain but make no progress.”[8] In the biblical journey through the wilderness, there are obviously none of these modern supports or amusements.

Having grown up in modern cities, most Americans haven’t experienced the rugged wild and so we don’t have much sense of the raw power of the elements. This is like a man who has never swam in the ocean against a strong current—he knows what currents are but he doesn’t fear them. Or like a child looking a candle who has never been burned.

Dante gives words to the feeling of a man who has experienced the wilderness:

Midway upon the journey of our life

I found myself in a dark wilderness,

for I had wandered from the straight and true.

How hard a thing it is to tell about,

that wilderness so savage, dense, and harsh,

even to think of it renews my fear!

It is so bitter, death is hardly more—

but to reveal the good that came to me,

I shall related the other things I saw.[9]

Dante includes us when he says “the journey of our life.” His experience is ours and so we should learn of him what the wilderness is like—savage, dense, and harsh.

The Wilderness Paradox

Life is a wilderness journey where we experience things we never would have expected and face difficulties that profoundly try us. But the paradox of the wilderness is that out of it, as Dante says, comes something good.

C. H. Mackintosh expounds on this paradox:

The trials of the desert put nature to the test; they bring out what is in the heart. Forty years’ toil and travail make a great change in people. It is very rare indeed to find a case in which the verdure and freshness of spiritual life are kept up, much less augmented, throughout all the stages of Christian life and warfare. It ought not to be such a rarity. It ought to be the very reverse, inasmuch as it is in the actual details, the stern realities of our path through this world, that we prove what God is. He, blessed be His name, takes occasion from the very trials of the way to make Himself known to us in all the sweetness and tenderness of love that knows no change. His loving kindness and tender mercy never fail. Nothing can exhaust those springs which are in the living God. He will be what He is, spite of all our naughtiness. God will be God, let man prove himself ever so faithless and faulty. This is our comfort, our joy, and the source of our strength.[10]

The Blessing of the Triune God

The reason that good can come out of desolation is that our entire wilderness journey is under a threefold blessing.

Jehovah bless you and keep you;

Jehovah make His face shine upon you and be gracious to you;

Jehovah lift up His countenance upon you and give you peace.–Numbers 6:24-26

Right before they set out God blessed His people, giving them a sort of divine bon voyage. Little do we realize at the time, however, that God has something much different than us in mind when He says bon (good). This is the good of Romas 8:28—”all things work together for good”—which is the good of gaining God Himself.

The blessing is not a smooth journey. As one hymn says, “God hath not promised smooth roads and wide, / Swift, easy travel, needing no guide.”

Another hymn I’ve always loved says:

Far too well thy Savior loves thee

To allow thy life to be

One long, calm, unbroken summer—

One unruffled, stormless sea.

Blessing is not the absence of problems; blessing is the presence of God. It is being mingled with God. And for that the wilderness does what maybe nothing else could ever do. It is God’s “severe mercy” to us to lead us through this howling waste, full of deserts and pits, drought and the shadow of death (Jer. 2:6).[11] God comes through it with us and through it God comes into us. Don’t waste your wilderness! Thank God for it and for what He can gain through it.

One of my first weeks of Bible college, one of my teachers said, “God gives you the training you need, not the training you want.” That has always stuck with me. It became a kind of aphorism that people would quote to resolve a conversation about a perplexing situation. God blesses us not with what we want, but with what we need, and His triune blessing is specifically designed for wilderness life. What we need on our journey is the Father’s keeping power, the Son’s gracious presence, and the peace of the Spirit’s countenance. He keeps our feet from slipping down a desert gorge. He supplies us with divine provisions when we cry out to Him. He grants us inward peace in the midst of wilderness terrors. But for these to become real and precious to us, we need a wilderness.

An Abstract of God’s Economy

The blessing in Numbers 6 is a doxological abstract of God’s economy. God blesses us through His processions in His economy. The All-sufficient God has come forth in the fullness of His being to be whatever we need. The Father is embodied in the Son and the Son is realized as the Spirit. The Father, in His naked essence, is invisible and unapproachable (1 Tim. 6:16). The Son is the face of God—His visible presence—and the Spirit is the countenance of the Son—His experienced presence. When God’s countenance reaches us it becomes our salvation. Psalm 42:5 speaks of “the salvation of His countenance,” which then in verse 11 becomes “the salvation of my countenance.” This is the Triune God in His economy dispensing Himself into us.

The unique blessing is God’s dispensing and dispensing produces mingling. But the greatest help to being mingled with God is our environment. Ron Kangas, speaking of Jacob, once said, “When we reach the point where deep within we accept the divine arrangement, the balance in our being will tip in favor of God, and the divine dispensing will go on without hindrance until we reach maturity upon maturity.”[12] Our environment opens us up to God’s dispensing like never before. It makes us desperate. Wilderness weakness produces desperation and desperation is the threshold of grace. Speaking about the smitten rock which flowed out water to drink, C. H. Mackintosh says that desert life “proves what is in us, and, thanks be to God, it brings out what is in Him for us.”[13] Don’t stop with the discouraging X-ray of what is in you; get to what is flowing out of God. What is in God for us is a bountiful supply.

1. Witness Lee, Life-Study of Numbers, p. 5

2. Origen, Homilies on Numbers, 1.3.7, 3.1

3. Hans Küng, On Being a Christian, pp. 413-414

4. Robert Alter, The Five Books of Moses: A Translation with Commentary, p. 871

5. ibid., p. 613

6. American Heritage Dictionary, 5th ed.

7. Alain de Botton, The Art of Travel, p. 164

8. Marcel Proust, Within a Budding Grove, p. 316

9. Dante, Inferno , lines 1-9

10. C. H. Mackintosh, Notes on the Pentateuch, p. 559

11. Augustine, Confessions, 8.11.25

12. Ron Kangas, “The Divine Intention, the Divine Economy, and the Divine Dispensing of the Divine Trinity, The Ministry of the Word, Vol. 18, No. 8 (Sept 2014), p. 54

13. Mackintosh, p. 560

This article has been much needed.

Have you read (or listened to) Art Katz? His sermons are on YouTube, SermonIndex.net and artkatzministries.org. With following your blog and reading the content, I believe you would find it challenging and edifying.

And, as far as novels, I recommend Thomas Wolfe (Look Homeward, Angel – Of Time and the River, etc.) if you haven’t already. Especially if you love Proust.

LikeLike

A journey with all the varied terrain. Lord cause us to see You and enjoy You on the way.

LikeLike

A wonderful view of the wilderness as it relates to our journey with the Lord today. How encouraging! Thank you brother for your labor in the Word.

LikeLike