Every now and then someone claims that Watchman Nee was anti-intellectual—that he devalued the role of the mind in the spiritual life and eschewed disciplined study of theology and Scripture. Instead of all this, he supposedly said that you only need to follow your inner light.

Nothing could be further from the truth.

A misinformed critique

As silly as it is, one often comes across this sort of caricature online. For instance, one (Baptist) website claims that Nee promoted

the idea that irrational inner voices or intuitions should be followed rather than the Bible as interpreted using the mind.1

The ridiculousness of this claim is baffling to readers of Nee’s theology. We say to ourselves, “Surely no one who has actually read Nee could think this.”

What Nee really thought

When we look at Nee’s writings a very different perspective appears.

Rather than downplaying the role of the mind, Nee actually said:

If a believer allows his mind to stop thinking, reasoning, and deciding, and if he does not compare his own experience and walk with that revealed in the Bible, he is inviting Satan’s deceptions to come into his mind.2

So it turns out that Nee holds the exact opposite view that the above website claims.

Nee continues: In following the leading of the Holy Spirit, Christians still need

to weigh, consider, or decide whether any seemingly God-given thoughts are according to the light of the Bible… Many believers think that their thoughts are hindrances to their spiritual lives. Little do they know that the real hindrance is when their head stops working or when it works in disarray.3

I won’t spend time on it, but it’s helpful to note that Nee identifies two potential problems here:

- When our head stops working

- When our head works in disarray

The first problem shows that the mind is central to the spiritual life and theological work. The second shows that, nevertheless, the mind needs to be in a certain condition (most fundamentally: renewed). Neither rationality alone nor spirituality alone is sufficient—Nee won’t allow us to play one off against the other. The spirit and the mind, he says, exist in a relation of “mutual assistance and reliance.”4

What’s more: Nee believed that as we advance in our spiritual life, our mind becomes even more employed and rational. He says:

When a believer’s mind has reached the point of being renewed, he will marvel at the capability of his mind… The believer’s concentration is more intensified, his understanding sharper, his memory stronger, his reasoning more precise, his eyesight farther, his work speedier, and his thoughts broader. 5

These quotes come from one of Nee’s earliest works, The Spiritual Man, written when he was 24 years old. If there were any place we would expect Nee to be idealistic, sloppy, or sensational it would be here, before he “grew up.” It’s typical for young Christians to have underdeveloped or extreme views that they later grow out of. But as it turns out, even in his earliest writings the claim that he held to an anti-intellectual view—denying or downgrading the role of the mind in the spiritual life—is simply false.

In his later works, he is consistent with this early position:

If we do not allow the Scriptures to dwell in our heart, it will be hard for the Holy Spirit to speak to us. Whenever God grants us a revelation, He does so through the words of the Bible.6

Nee’s position is consistent across time. He wasn’t uncritical in his youth, and he didn’t become unhinged with age. For Nee, spiritual leading, light, and revelation are not irrational or suprarational experiences independent of and antithetical to clear-minded understanding of Scripture.

A Better, Scholarly View

In a recent article, Pan Zhao rejects the anti-intellectualist view of Nee, saying

Nee’s theology often attracts criticism of anti-intellectualism due to its perceived negative attitude toward reason and knowledge. However, this criticism stems from the fact that some scholars have only focused on the first half of Spiritual Man, while overlooking the theological insights presented in the second half, which emphasizes the role of mind and will.7

In other words, only a partial and lopsided reading of Nee could come to the conclusion that he devalued the role of the mind or that he did not promote serious study of Scripture. The problem is not with Nee’s teaching; the problem is with selective reading of Nee.

The problem of selective reading is a common problem in evaluating thinkers who produce a large corpus—whether unwieldy or unsystematic—or whose views develop over time. The same problem has been noted in studies of Karl Barth. As John Webster says,

Barth’s work has always suffered from partial readings which expound or criticize his thought on the basis of only a selection from his corpus.8

Barth and Nee have both suffered from selective and fragmentary readings. Dabblers beware!

In another recent book chapter, Brian Chu clarifies Nee’s position on the role of the mind in the spiritual life:

spirituality and rationality are not an either-or relationship; rather, they are both indispensable for spiritual life and mutually influencing and complementary to one another.

…labels such as “anti-intellectualism,” “spiritualism,” “subjectivism,” and “body-soul dualism”… should be reexamined and removed.9

The charge that Watchman Nee was anti-intellectual simply does not survive engagement with his actual writings. From his earliest work to his mature thought, Nee consistently insists that spiritual discernment requires an active, disciplined, and renewed mind—one keyed to Scripture, active in judgment, and alert to self-deception. In fact, when one actually looks at the chapters on the mind in The Spiritual Man, Nee’s repeated concern is to highlight the dangers of a passive mind!

Even a quick survey of Nee’s writings, however, would seem to immediately debunk this entire claim.

For instance, Nee conducted verse-by-verse commentaries on the books of Matthew, Revelation, and (his greatest!) Song of Songs.10 He undertook a theological exegesis of both Romans and Genesis. Furthermore, three volumes in his collected works are devoted to Notes on Scriptural Messages. Finally, he literally published a book called How to Study the Bible!

Nee’s entire theological and ecclesiological work grew out of sustained, rigorous interpretation of Scripture: “mindfulness” in the most theological sense. Anyone who says otherwise is fooling you.

Nee’s Method for Theological Study

Not only was Nee not anti-intellectual, he outlined and recommended his own method for studying the Bible.

He details this at length in his book How to Study the Bible. But an even more convenient and concise place to see this is in two short talks he gave on Aug 31, 1949 and Feb 18, 1950,11 two years before his imprisonment by the Chinese Communist government. Here, Nee recommends a disciplined and academic approach to studying Scripture—one that demands careful historical, philological, and theological research, i.e., the use of your mind! And not just your mind, but engagement with the great theological minds of the past.

At the end of the second talk, he says,

Both Brother Witness and I study the Bible according to the above method. I hope that some brothers and sisters will put forth the effort to study the Bible this way.12

Both talks offer valuable insights into Nee’s theological method. The important thing to note here is how much it tallies with a modern scholarly approach (with one potential caveat, point 7 below).

Here are the steps he outlines in studying the Bible.

1. Study the Text in the Original Language

In studying the Word we have to pay attention to the original text.13

Nee insists that serious Bible study must start as close to the text as possible—not by looking up to the sky but by looking down at the page. This means, first, that one must read, or at least closely work with, the original language and even “translate it from scratch.”14

Working with the original language is slow and careful work, but it is essential. Nee stresses that careless familiarity with Scripture is one of the great dangers for Christians who think they already “know” the Bible. “If we are not careful and serious in our study of the Word, we can easily build a message upon a wrong translation of a word.”15

The Recovery Version embodies the legacy of Nee’s sensitivity to the original language in numerous passages. This can be seen in its handling of words like economy (Eph 3:9), tabernacled (John 1:14), soulish (1 Cor 2:14; Jude 19), and even basic prepositions like believe into16 (John 11:25). While these four translations decisions are not well-represented in English versions, they are obvious in the Greek and readily acknowledged in commentaries.

Just one comment on the RcV translation of “soulish” in Jude 19, for instance (“These are those who make divisions, soulish, having no spirit.”).

In his recent translation of the NT, David Bentley Hart translates this verse as follows: “These are those who cause divisions, psychical men, not possessing spirit.” He then says in a footnote,

Despite its long history of often vague and misleading translations, this verse clearly invokes the distinction between psychē and pnevma (soul and spirit) as principles of life, and between “psychics” and “pneumatics” as categories of persons.17

Of course, this simply goes back to (Paul!) Origen, who says:

I have noticed a distinction between soul and spirit in all Scripture. The soul is something intermediate and capable of both virtue and evil, but the spirit of man is incapable of receiving things that are inferior.18

Hart says that he takes Jude 19 as “a sort of ‘acid test'” in evaluating English translations, since it is “a verse whose meaning is startlingly clear in the Greek but which no collaborative translation I know of translates in any but the vaguest and most periphrastic manner.”19

The RcV, as it turns out, has passed this acid test since 1984.

2. Compare Multiple Translations

The worst thing is for a person to have only one version and to treat it as a foolproof text.20

Next, one should compare a number of English translations to get a sense of previous renderings of the text, including common translation options and solutions to tricky or ambiguous passages. This is a way to sort of triangulate the meaning of a passage and how certain renderings strike an English reader and capture the sense of the Greek. Notice how different versions handle technical terms, syntax, clarity, readability, and style.

This will also highlight what popular versions commonly miss and what popular level readers assume the verse says. A glaring example of a translation that in itself and its historical context was not wrong but today can be very misleading is the KJV translation of John 14:2—In my Father’s house are many mansions.21

Nee strongly warns against relying on a single English version. He recommended comparing five different versions. While Nee highly valued Darby’s translation, he was also consulting the hottest new English versions, like James Moffatt’s modern translation.22 It’s important to compare translations that have enough meaningful difference so that you get a feel for the variety that’s out there.

3. Paraphrase the Text

Paraphrasing means rewriting the words of the Bible in language that can be easily understood.23

The next step is to paraphrase the text, putting the sense of the passage in your own voice and into a more colloquial manner of speaking, while retaining the tone and meaning of the passage. Paraphrasing lies midway between exposition and translation.24

The point of this step is to zoom out so that you don’t get lost at the granular level of technicalities. This step ensures you have a good grasp on the thrust of the passage and the main ideas.

For Nee, paraphrasing is not dumbing Scripture down—it is a test of whether we actually understand what we have read.

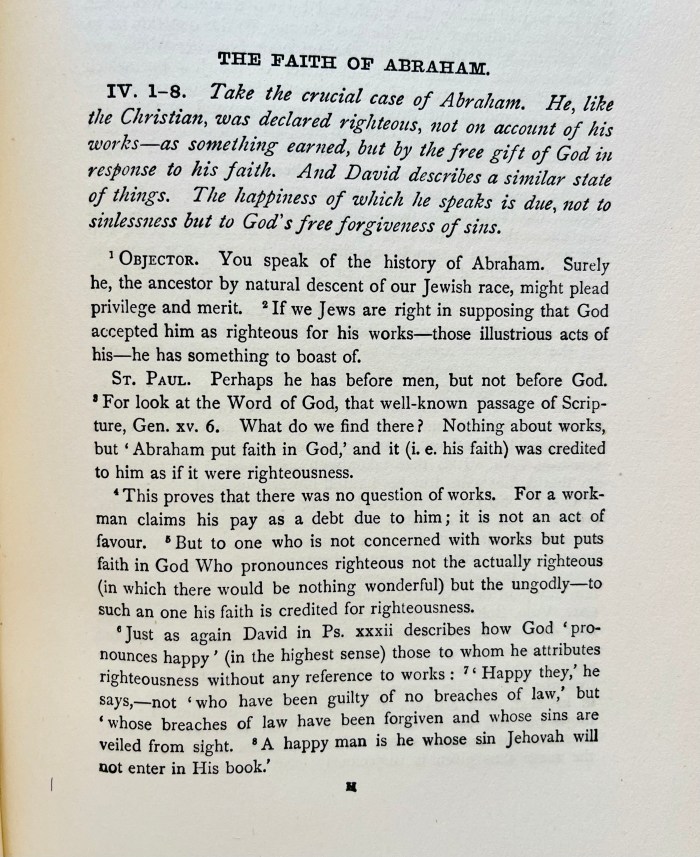

Some people may not realize that this was typical scholarly practice for a while. Look at Sanday and Headlam’s well-respected commentary on Romans (ICC) from a generation ago. They always start a passage by offering a paraphrase of the text. The picture is their paraphrase of Romans 4:1-8.

4. Do in Depth Word Study

We have to study every word and phrase in every passage carefully and thoroughly.25

Nee says, in another place, that there are 200-300 words that require in depth study.26 We should study how often particular expressions are used in Scripture and the circumstances and background in which they are used. This yields “a basic and clear understanding” of the original sense of the word, since words have histories, ranges, and patterns of use. Meaning emerges from contextual and historical usage. Nee warns against cutting corners here, “Do not take any expression for granted.”27

Nee highly relied on the textual work and technical exegesis of Henry Alford, Christopher Wordsworth (more on him below), and Samuel Thomas Bloomfield—some of the top scholarship of his day. Also, all of them were Anglicans—a good reminder that one should read across denominational lines and take the good wherever it can be found. The point is not to limit ourselves to using the resources that Nee used, but to understand the principle of utilizing the most up to date scholarly studies. This would include using lexicons, concordances, and theological dictionaries, such as BDAG.

Studying individual words in detail will exposes some of the places we import historical vagueness, modern assumptions, and inattention to contextual nuance. Here Nee is resisting the kind of impressionistic reading that goes no further than saying “to me it means…” I.e., he is explicitly resisting “irrational inner voices or intuitions.”

5. Synthesize Scripture with Scripture

Through synthesis we can trace a line through the Bible.28

If step four gave us depth, this step gives us length. Local meaning and context should be integrated with insights spanning the whole canon, tracing the echoes and resonances of key words and concepts. This gives canonical fullness to our understanding of things like covenant, redemption, holiness, the work of the Spirit, etc.

In this section we compare Scripture with Scripture, clarifying the obscure with the plain,29 deepening the literal with the spiritual,30 differentiating law and gospel and righteousness and grace, distinguishing the trunk from the leaves and branches,31 noting the development of seed to harvest, tracing the theo-logic and arc of God’s economy, and applying the rule of faith32 to the unruly jungle of discourses.

This is where Nee’s method moves beyond analysis to theological coherence: meaning unfolds across the whole canon. If we neglect synthesis, we will be forced to “wander through the Word mindlessly” and we will “gloss over everything indiscriminately.”33 Or, we will only have a piecemeal understanding.

6. Read Commentaries and the Classics of Theology

After studying the text, we should study the expositional writings of a few writers, as well as the commentaries.34

Nee places strong emphasis on historical study. He begins one of the talks I’m drawing from by saying:

In studying the Bible it is crucial that we not despise “the light from the prophets.” We should not despise the light our predecessors have gained. Throughout the ages many people have learned many things… They have received much enlightenment… We have to look up and study their work.

In other words, Nee was no self-made thinker, no lone explorer, “no genius rejoicing in his own creative ability.”35

He wasn’t a theological comet—blazing out of the darkness all alone, a self-contained reference point blinded by his own glow—he was a star in a greater theological constellation.

He was a student of theology, a listener to the minds of the past, a reader of other’s writings. He thought along with others, even if later he thought beyond them. In fact, the attitude that we do not need to read beyond the writings of our own tradition is, according to Nee, a sure sign of the sickly pride of Laodicea.36

In his famous biography of Augustine, Peter Brown notes:

As with many immensely fertile thinkers, it is difficult to imagine Augustine as a reader. Yet, what happened at this crucial time [of intellectual formation], and in the years that follow, was a spell of long and patient reading… a reading so intense and thorough that the ideas… were thoroughly absorbed, ‘digested’ and transformed.37

In other words, the theological greats of the church all begin by reading greatly. Nee was no different.

He was a prolific reader. By 1925, when he was still in his early twenties, (three years before he published The Spiritual Man) his theological library had already grown to three thousand books. It’s reported that, in his early ministry, he spent one-third of his income for personal needs, one-third for helping others, and one-third to buy books. By the age of 23, his small bedroom had become less a place for sleeping than a private library—stacks rising from the floor, lining the walls, narrowing the space around his bed into a maze of paper.38

His personal library contained “nearly all the classical Christian writings from the first century on.”39 Certainly this would have included the Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, which had just been published between 1886 and 1900. Beyond specific titles, the categories included “books of the church fathers, books about church history, books of Bible scholars, and biographies of famous Christians with many of their good messages.”40 A little bit of everything, or should I say, lots of everything.

To read the works of others and not just the Bible itself is to recognize that we are not the first ones to interpret the Bible. That we stand on the shoulders of those who come before us. That we see ourselves as part of the same conversations that Origen and Augustine, Luther and Barth were having.

This is not a replacement for rigorous engagement with the text itself, but a safeguard and enrichment. Nee insists that private illumination at odds with the church’s accumulated insights is unreliable. Even more, it is an offense against the principle of the Body—not receiving the gifts of another member is rejecting the riches of the Head.41 When we aren’t open to what those before us have seen, experienced, and committed to writing, “the church is dragged into poverty.”42

I mentioned Nee’s use of Christopher Wordsworth’s biblical scholarship above. He was an Anglican Bishop (d. 1885), who wrote a full textual commentary on the Bible. The fact that Nee used his work is particularly interesting because of Wordsworth’s practice of quoting church fathers in full in his commentary and not just cite them (similar to something like Barth’s use of Heinrich Heppe’s Dogmatics). Wordsworth’s biographers note that, opening Wordsworth’s commentaries, “The first thing that strikes us is the extraordinary wealth of patristic learning with which he fortifies his interpretations.”43 In Wordsworth, Nee would have access to a distillation of the insights from patristic theologians tied to specific passages of Scripture (much like today’s series, Ancient Christian Commentary on Scripture). This is just one specific instance of how Nee drank deeply from the wells of theological tradition.

7. The Need to be Spiritual

One must read the Bible with his spirit and in the realm of spirit. No matter how educated, logical, and analytical a man is, he cannot understand the Bible if he does not have this spirit.44

The final aspect of Nee’s theological method is actually the one he lists first in How to Study the Bible.

To study the Bible as the Word of God, to understand God’s word and to experience illumination and life, we have to be the right kind of person—a spiritual person (hence the title of one of Nee’s well-known books, The Spiritual Man). In Nee’s shorthand formula: “The kind of person we are determines the kind of Bible we read.”45

Nee is not simply against the so-called theologia irregenitorum46 (a theology of the unregenerate) but, even more, against the thought that as long as we have the right external resources and a clear head we can understand the heart and heartbeat of Scripture. Nee sounds very much like Karl Barth when he says, “Only God can speak God’s word.”47 God’s word is spirit and life—not everything can be resolved by knowing Greek and Hebrew.48 One must become the right kind of person and not just adopt the right kind of methods. One must be spiritual.

Nee is simply echoing a basic concept in patristic theology. It is well-represented by Gregory of Nazianzus when he says,

Discussion of theology is not for everyone, I tell you, not for everyone—it is no such inexpensive or effortless pursuit… It is not for all people, but only for those who have been tested and have found a sound footing in study, and, more importantly, have undergone, or at the very least are undergoing, purification of body and soul. For one who is not pure to lay hold of pure things is dangerous, just as it is for weak eyes to look at the sun’s brightness.49

Conclusion

Watchman Nee, then, is not anti-intellectual but anti-reductionist. We have to bring our best scholarly tools to the text and train our minds how to think in conversation with those who have interpreted the text before us. However, the Bible, as divine revelation, yields itself most fully to those whose minds are renewed and whose lives are being purified—to those becoming the kind of people capable of hearing God speak.

At the end of the day, for Nee, theology is not simply an academic discipline but a mode of participation in God.

The Word of God is spirit and life—the Word of the true and living God. Its depths are an unfathomable ocean, a mystical forest, a labyrinth of light.

It is not pried open by linguistic crowbars alone.

We bring the best resources at our disposal to the text, but we neither begin nor end with tools. We begin with prayer, humility, and purity of heart, and we end where Scripture itself ends: incorporation into God through Spirit and the Word.

- See also, Dongsheng John Wu, Understanding Watchman Nee: Spirituality, Knowledge, and Formation (Wipf and Stock, 2012), 5: “Nee’s thought can be shown to be not, as some of his critics perceive, anti-intellectual, but rather, in congruence with the Christian mystical tradition.” This is true, but it ignores Nee’s equal emphasis on rational methods of theological study. ↩︎

- Watchman Nee, CWWN 14, “The Spiritual Man,” pp. 512-513. ↩︎

- Ibid., 513-14. ↩︎

- Ibid., 560. ↩︎

- Ibid., 559. ↩︎

- CWWN 54, p. 82 ↩︎

- Pan Zhao, “Is the Spiritual Man Pentecostal? Watchman Nee’s Perspective on the Charismatic Experiences,” Religions (Basel) Vol. 14, Iss. 7, (2023): 833. PDF p. 13. ↩︎

- John Webster, Barth, 2nd ed (Continuum, 2004), 141. ↩︎

- Brian Siu Kit Chiu, “The Sinicization of Christian Pietism: Jia Yuming’s and Watchman Nee’s Approaches to the Problem of ‘Rationality versus Spirituality,’” in Modern Chinese Theologies: Volume 2: Independent and Indigenous, ed. Chloë Starr (Fortress Press, 2023), 155-56. ↩︎

- See Paul HB Chang, “The Spiritual Human is Discerned by No One”: An Intellectual Biography of Watchman Nee, unpublished dissertation (Univ of Chicago, June 2017), 45: “only three biblical books he ever attempted to explain in its entirety.” ↩︎

- These can be found in Nee, CWWN 61 and 62. ↩︎

- CWWN 62, pp. 297-98. ↩︎

- Ibid., 295 ↩︎

- CWWN 61, p. 43. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- See Martin H Fuller and Mitchell J Kennard, “Milestones: ‘Believe into,'” Affirmation and Critique Vol. 30 (2025), 84-91. ↩︎

- DB Hart, The New Testament: A Translation, 2nd ed (Yale Uni Press, 2023), 495. ↩︎

- Origen, Commentary on John, 32.218. ↩︎

- Hart, The New Testament, xviii-xix. ↩︎

- CWWN 62, 297. ↩︎

- This translation was retained in the NKJV (1982). ↩︎

- CWWN 17:71. ↩︎

- CWWN 62 296. ↩︎

- CWWN 54:93. ↩︎

- CWWN 61:44. ↩︎

- CWWN 54:135. ↩︎

- CWWN 61:44. ↩︎

- Ibid., 45. ↩︎

- See Augustine, De doctrina Christiana 2.9.14: “One should proceed to explore and analyze the obscure passages, by taking examples from the more obvious parts to illuminate obscure expressions and by using evidence of indisputable passages to remove the uncertainty of ambiguous ones.” ↩︎

- See Origen, De Principiis 4.3.11: “The very soil and surface, so to speak, of Scripture, that is, its reading according to the letter, is the field… while that deeper and more profound spiritual sense is that very hidden treasure of wisdom and knowledge… which, for them to be found, requires the help of God.” See also Augustine, Confessions 12.14.17: “What wonderful profundity there is in your utterances! The surface meaning lies open before us and charms beginners. Yet the depth is amazing, my God, the depth is amazing.” ↩︎

- CWWN 54:38. ↩︎

- See Irenaeus, Against Heresies 1.9.4–1.10.1 and The Demonstration of the Apostolic Preaching 6. ↩︎

- CWWN 61:46. ↩︎

- CWWN 62:297. ↩︎

- Friedrich Zündel, quoted by Karl Barth in his Romans commentary, 27. ↩︎

- CWWN 47:84-85. ↩︎

- Peter Brown, Augustine of Hippo: A Biography, 94-5. ↩︎

- Lee, Watchman Nee: A Seer of the Divine Revelation, 25. ↩︎

- Ibid., 25. ↩︎

- Witness Lee, CWWL, 1985.4, 171 ↩︎

- CWWN 47: 173-75. ↩︎

- Ibid., 174. ↩︎

- John Henry Overton and Elizabeth Wordsworth, Christopher Wordsworth, Bishop of Lincoln, 1807-1885 (Rivingtons, 1888), 412. ↩︎

- CWWN 54:11. ↩︎

- Ibid., 25. ↩︎

- See Karl Barth, CD I/1, 18-21; and also, Barth in Conversation, Volume 3: 1964-1968 (2019), 54. For the contrary view, see Paul Tillich, Systematic Theology, vol 1, 10-11. ↩︎

- CWWN 53:95. Cf. Karl Barth, The Göttingen Dogmatics, trans. Geoffrey W. Bromiley (1924-25; Wm. B. Eerdmans, 1991), 272: “Only God can talk about God.” ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Gregory of Nazianzus, Oration 27.3. ↩︎

Amazing and so so enlightening piece of writing! I’ve really enjoyed reading it!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for reading!

LikeLike