This post is an attempt to think through Witness Lee’s interpretation of Romans 1:3-4. These verses function as Paul’s opening statement about the gospel in his letter to the Romans. Paul says that the gospel concerns

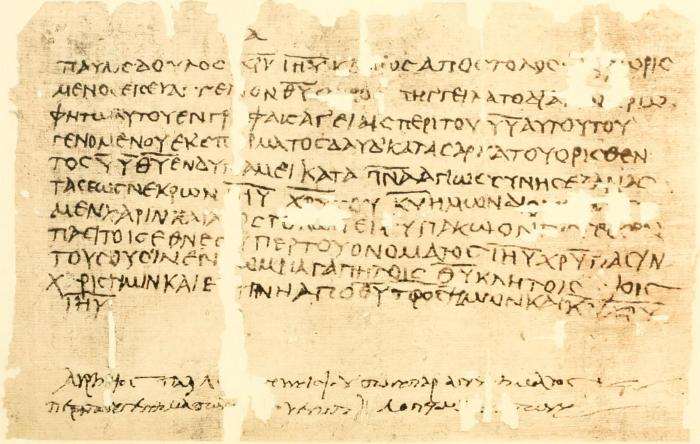

God’s Son, who came out of the seed of David according to the flesh, who was designated [ὁρίζω] the Son of God in power according to the Spirit of holiness out of the resurrection of the dead, Jesus Christ our Lord.

Lee takes the two halves of Romans 1:3-4 to indicate “the sequence of Christ’s [historical] process,” the two natures of Christ, and the prototype of Christ for the goal of the gospel.1 According to Lee, the genuine, intrinsic, highest, and fullest gospel2 is the gospel of God’s economy, “the gospel of sonship,”3 i.e., the gospel of ecclesial deification.4 While Lee recognizes the centrality of 1:17, the banner verse of the Reformation, he also strikingly says that, “In a sense, the entire book of Romans is structured around these phrases. Verses 3 and 4 of chapter one actually summarize the whole book.”5

Jesus was designated the Son of God “in power.” As the subsequent argument of Romans indicates, however, the interest in “power” is more than christological, for the thesis of Romans is that the gospel about Christ is “the power of God unto salvation.”6 In fact, the words power, Spirit, holiness, and resurrection are central to the theological thrust of the good news that Paul announces in this letter, as Lee notes: “The first four verses of Romans are extremely important,” for they “contain many key words” that are central to Paul’s argument.7 I like how Matthew Bates put it: “Since the true content of Paul’s gospel itself is at stake, a proper unpacking of this tightly compressed statement is urgent.”8

The Text

Many scholars take Paul to be quoting and amending an early Christian creed in vv. 3-4.9 Robert Jewett cites 12 reasons for thinking this.10 Some of the reasons he cites have more weight than others, some look like throwing spaghetti at a wall to see what sticks, BUT the cumulative force is impressive and convincing enough for me.11 The clearest reason is the structure of these verses, as Jewett notes: “The cogency of these observations may be most easily grasped when the structure of the passage is made visible.”12 The passage is composed of juxtaposed pairs—became/designated, seed of David/Son of God, flesh/spirit, birth/resurrection—and exhibits a tightly constructed, carefully balanced parallelism, which is typical of liturgical use:

The biggest question for exploring Lee’s interpretation of this passage centers on the meaning of the participle (a verbal adjective) in verse 4, where “the emphasis” of this confession lies—who was designated (τοῦ ὁρισθέντος).13 This line “is decisive for interpretation of the whole.”14 What does it mean that God’s Son, after being born as a descendant of David, was designated the Son of God in power in resurrection?

Beverly Gaventa echoes a widespread sentiment when she says: “Almost every word in this verse [v. 4] challenges interpreters.”15 The main interpretive options will be explored below. But as I hope to show, Lee offers a compelling perspective of what these verses mean and how they relate to the whole of Romans. In particular, Lee’s interpretation draws upon the classic reformed position but critically modifies it in alignment with patristic sensibilities.

The Importance

Lee stresses numerous times how important the concept “designation” is. He repeatedly spoke on this theme throughout his ministry. In his Life-Study of Romans (1974), he devoted 7 messages to it, both as it relates to Christ and as it relates to our spiritual experience. The designation of the Son of God was one of the three aspects of what he called “the intrinsic significance of Christ’s resurrection.”16

Lee says that the meaning of designation is “very, very deep,”17 it is “very significant,”18 it “implies a great deal” and “would require at least ten books to fully expound the intrinsic details implied in this word.”19 Distinguished NT scholar Martin Hengel substantiates such imagined prolixity, saying in 1976 that, “In recent years, more has been written about this than about any other New Testament text.”20 And yet Lee admits that “it is hard to say what the word designated means in Romans 1:4.”21 And further: “This is one of the hardest points in the Bible for us to understand.”22 Even the great Origen confessed that the meaning of this verse was “something that constrains our comprehension.”23

The Meaning

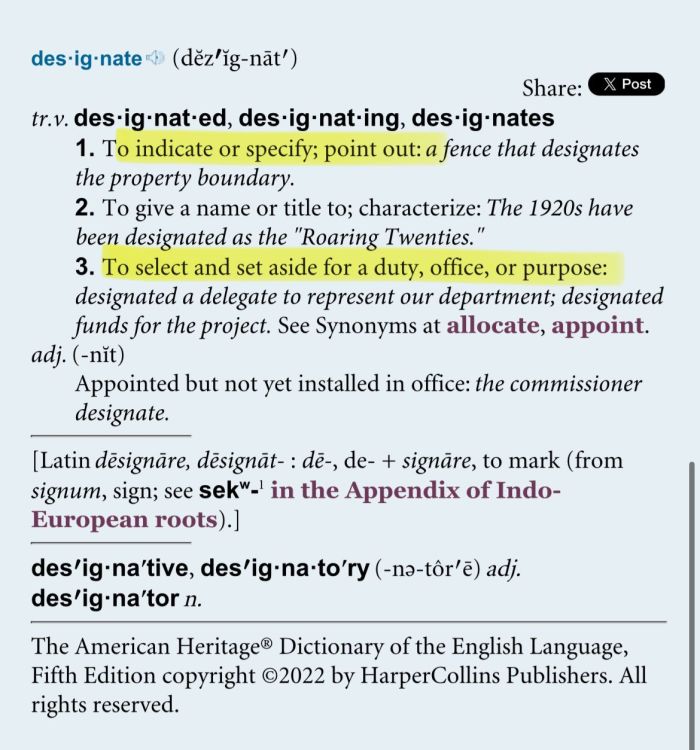

The word designated is a translation of the Greek verb ὁρίζω (horizo), which occurs 8x in the NT, with slightly different denotations (Luke 22:22; Acts 2:23; 10:42; 11:29; 17:26, 31; Rom 1:4; Heb. 4:7). As a friend pointed out to me, it is where we get the English words horizon, aphorism, and aorist.

These English words hint at the Greek’s basic meaning of “marking out,” whether conceptually, spatially, personally, or vocationally.

The use of this word, which appears nowhere else in Paul’s writings, supports the theory that we are dealing here with a pre-Pauline creedal snippet that Paul has modified to fit “within the framework of his own theology”24 for his purposes in this letter. While speculative, Jewett proposes a three-stage development of this composite confession, representing early Jewish Christian, Hellenistic Christian, and finally Pauline interests.25

The fact that Paul adopts, modifies, and puts to use terminology not his own perhaps allows room for taking it, as Lee does, for more than the Greek alone might indicate. Lee, in fact, draws a distinction between the word itself and the fuller implications of the word: “The word designation may seem common to you, but the point is not common.”26 In other words, he seems to be saying, “Linguistics doesn’t exhaust theology.” Sanday and Headlam offer a perceptive insight that also opens up space for interpretative expansion. They judged that “The word itself does not determine the meaning either way: it must be determined by the context. But here the particular context is also neutral; so that we must look to the wider context of St. Paul’s teaching generally.”27

In a more recent article, Joshua Jipp, who like Lee thinks Rom 1:4 functions to “foreshadow the manner in which Christ’s sonship is the prototype for the rest of humanity,”28 says:

Despite what some of the ancient and modern interpreters claim, there is nothing inherent in the words of Rom 1:3-4 that necessarily determines their meaning or precludes the use to which they have been put… Attending to the way the words run will not give one any secure purchase, for example, as to… how one should read horizo. An examination of ancient and modern readings suggests that answers to these questions depend upon the framework within which they are read.29

Three Possible Meanings in Romans 1:4

What could ὁρίζω mean in Romans 1:4? Godet outlines the possible significances of ὁρίζω with admirable crispness.30 The “marking out” may be:

- In thought—translated as “to destine to, decree, decide”

- In words—translated as “to declare”

- In an external act—translated as “to install, establish, or demonstrate by a sign”

Godet argues for the third option. He thinks the first is “incompatible” with the clause in v. 4, “out of the resurrection,” since it is “impossible that the divine decree relative to the glorification of Jesus should be posterior to his mission to the world.” The second is “insufficient” in the context, since “the resurrection not only manifested or demonstrated what He was; it wrought a real transformation in His mode of being.” Hengel agrees on this point: “to talk of Jesus as Son of God is at the same time to make a statement about the ‘transcendent’ being of the risen Christ with God in his glory, into which he has been ‘transformed.'”31 For Godet, then, ὁρίζω is neither God’s decision about the destiny of the Son nor God’s announcement about the identity of the Son; it is a transformative action upon the Son.

Lee highly respected Godet and used his commentary when studying Romans.32 He picked up on Godet’s third option but applied it in a different sense, more in line with Gregory of Nyssa. Godet took the third option to mean that Christ was restored to his position as Son of God that he had renounced in his incarnation, ie, the transformation was positional. He differs from position three below, most especially the ESV Study Bible note, in that he does not think Son of God here refers to the official name of the messianic king. For Godet says that “to beget (Psalm 2:7) never signifies to establish as king; the word denotes a communication of life.” And a little bit further on: “resurrection is to Jesus, as it were, a second birth.”33 Lee picks up on all these insights but takes them to mean that in resurrection Jesus’ humanity was “sanctified, uplifted, and transformed.”34 (More on that in a moment). In other words, Lee folds the full significance of glorification into the word designation.35 Lee of course, holds that Christ was installed as king but connects this technically with the ascension. Lee distinguishes between resurrection and ascension as between life/power and position/authority.

Either way, the word (ὁρίζω) clearly indicates some sort of change, as all verbs do. Sometimes the simplest verb can encompass a profound and complex change. I think of Gérard Genette’s famous summary of Marcel Proust’s seven volume novel, In Search of Lost Time: “Marcel became a writer.”36 The verb hints at, but barely conveys by itself the staggering involvements of what happened. The only way to really understand what this means is through conceptual and narrative amplification. The verb states a fact but doesn’t explain how a fact obtains.

While explaining how is a temptation for theologians and where they sometimes get into trouble, explanation must often be risked but only up to a certain point. As my former teacher George Hunsinger loves to modify Anslem’s famous aphorism: “faith seeking the limits of understanding.” Gregory of Nyssa himself, whose view on designation we will encounter soon, said: “We are unable to detect how the divine is mingled with the human. Yet we have no doubt [that it happened]… But how this happened we decline to investigate as a matter beyond the scope of reason.”37

Something momentous has happened in resurrection to the Son of God, the seed of David. What happened? Let’s revisit the options but now with some amplification. I would summarize the options in the following way.

1. Change in essence or form. “Now he is what he formerly wasn’t.”

a) Adoptionism

This could be taken in two ways. If it is taken as classic adoptionism (as if a person or human messiah becomes Son of God for the first time), the church has resisted this interpretation as heretical from the get-go. Early proponents of this position include Theodotus of Byzantium and Paul of Samosata. Many modernist interprets hold this view as well, invoking Acts 2:36 (another supposedly adoptionist text) as the interpretive key to Romans 1:4.38 Rudolf Bultmann claims that “the earliest Church called Jesus the Son of God because that was what the resurrection made him.”39 Bart Ehrman has recently upvoted this position in his book How Jesus Became God.40

Adoptionism is rejected by Paul, (even if we concede that it was possible to read it that way in the creed he adapted, again, which is speculative), because verse 3 says that Christ was already God’s Son before he came out of the seed of David. So also in Romans 8:3: “God sending his own Son in the likeness of the flesh of sin.” If the Son was sent to be incarnate, then clearly the Son existed before incarnation, baptism, or resurrection (the different moments that some claimed an adoption occurred). If I send you a gift, clearly the gift exists before I send it. Doug Moo nicely summarizes Paul’s view on this: “It is the Son who is ‘appointed’ Son,” thus ruling out any notion of adoption here.41

b) Not adoptionism

The second way this could be take is exemplified by Richard Gaffin, who affirms Christ’s preexistent sonship, ie rejecting the adoptionist heresy: “Christ’s resurrection is not evidential with respect to his divinity but transforming with respect to his humanity… At the resurrection Christ began a new and unprecedented phase of divine sonship. The eternal Son of God … has become what he was not before.”42 This last sentence is problematic if taken to mean that “the eternal Son” changes. But his notion of the transformation of his humanity is right on and to explore this more we turn to Origen and Gregory of Nyssa.

Origen and Gregory of Nyssa, both firmly rejecting adoptionism, will say something similar to Gaffin’s first half. They think of resurrection as the ultimate permeation of divinity into Jesus’ humanity, developing a “transformative Christology”43 or christology with a “progressivist logic.”44

Origen

In his commentary on Romans 1:4, Origen says that Hebrews 2:10— ‘It was fitting that he, through whom and in whom all things exist, in bringing many sons to glory, should make the author of their salvation perfect through sufferings’—is a key to understanding Romans 1:4. This is because resurrection is the end of Christ’s sufferings (Rom 6:9), after which we no longer know Christ according to the flesh (2 Cor 5:16). Origin then draws a cryptic conclusion: “therefore everything that is in Christ is now the Son of God.”45 The editor of this volume notes that this apparently means that “after the resurrection Christ, in all his aspects, i.e., body/flesh, soul, spirit, may now be designated the Son of God or Logos.” The editor then tells us to compare this with what Origen says in another place: “We affirm his mortal body and the human soul in him received the greatest elevation not only by communion but by union and intermingling, so that by sharing in His divinity he was transformed into God.”46 In his commentary on John 12 (“now is the Son of Man glorified”), he says something similar: “the exaltation of the Son of man… lay in this, that He was no longer other than the Word but identical with it… the humanity of Jesus became one with the Word.”47

To sum up: Origen thinks that, while always being the Son of God,48 the flesh of Jesus was transformed into God in the resurrection and this is related to leading many sons into glory through a perfected Savior. This is not adoptionism, but it does seem to point to some kind of change of essence (this may not be the best word) or quality or form of Jesus humanity. Not that the humanity wasn’t humanity anymore, but that it was “changed into an ethereal and divine quality.”49

Gregory of Nyssa

Gregory of Nyssa holds a similar view to Origen but more explicit and more developed. The most significant passages are in To Theophilus,50 Against Eunomius 3.3,51 and Antirrheticus against Apollinarius.52 In these passages he is countering multiple heretical teachings, 1) Eunomius’ claim that the Son is not of the same divinity as the Father, cf Acts 2:36, 2) Apollinarius’s claim that the humanity of Jesus was incomplete and 3) that there are, in effect, two Sons, ie adoptionism.

The important point for us here, is nicely summarized by Sarah Coakley: “Gregory’s entire christological project assumes that the task of the incarnation is the gradual purgation and transformation of the nature of the human in Christ… in the resurrection.”53 Coakley continues: “This particular ‘mingling’ of divine and human in Christ… is one in which we are also destined to participate: it is the ‘first-fruits’ of ‘them that slept’, and hence the union (or ‘mingling’) of human and divine that occurs in Christ is what enables our final union with Christ.”54 Thus for Gregory, the nature and extent of our salvation flows from the metaphysics of christology. Although Gregory is not actually commenting on Romans 1:4 here, like Origen was, in Contra Eunomius he is at length commenting on Acts 2:36, which we have already seen is a similar sounding “adoptionist” text which also has to do with resurrection. Because of this, I think it is appropriate to apply his views on this text to Romans 1:4 as well, as it is also about the resurrection.

Here are some key quotes from Gregory, all about what happens in the resurrection of Jesus:

“Everything that was weak and perishable in our nature, mingled with the Godhead [θεότητι], has become that which the Godhead [θεότης] is.”55

“The ineffable economy [is that] the Right Hand of God, who made all things that exist… himself elevated to his own lofty height the human being who was united with him, by making him to be what he himself is by nature through the commingling.”56

“The flesh is not identical with the divinity, before it was transformed to divinity.”57

Another key here is a thought going back to Athanasius that the incarnation refers to the whole span of Christ’s earthly existence from conception to resurrection. John Behr frequently makes this point:

The Lord’s coming in his body… is not something that can be reduced solely to his birth from Mary. He does not preemptively transform all the human possibilities simply by taking a body, by being born, for otherwise he would not actually have undergone them. Rather, the “Incarnation,” the “coming” of the Lord or his “parousia,” encompasses his whole life, so that, for Athanasius, Christ really did grow in wisdom, suffer hunger and fear, and ultimately die on the Cross. Christ really does appropriate the suffering that belongs to the human nature which has become his own; he suffers, as Athanasius repeatedly states, while also insisting that Christ’s appropriation of this suffering is simultaneously its reversal, transforming suffering into impassibility.58

2. Change in appearance or recognition. “Now we see what we formerly didn’t.”

The translations that capture this meaning would include “declared, shown to be, demonstrated.” On this view, the eternal Son of God who assumed flesh in the incarnation was newly perceived to be what he already was. Representative scholars who adopt this view include Ambrosiaster, Chrysostom, Theodoret of Cyrus, Calvin, Alford, Darby, Sanday and Headlam, Gaventa.

This view is pretty straightforward, so I will just present a selection of quotations. Alford and Darby are significant here for situating Lee’s interpretation because, even more than Godet, Lee took them as life-long interlocutors, even though he disagreed with them in significant ways, as will be the case in the interpretation of these verses.

Ambrosiaster: “He who was incarnate, who obscured what he really was, was then predestined [per the Vulgate] according to the Spirit of holiness to be manifested in power as the Son of God by rising from the dead… For every ambiguity and hesitation was made firm and sure by his resurrection.”59

Theodoret of Cyrus: “Before his crucifixion and death the Lord Jesus Christ did not appear to be God either to the Jews or even to the disciples. For they were offended by human things, as when they saw him eating and drinking and sleeping and urinating… But after he rose from the dead… all those who believed recognized that he was God and the only begotten Son of God.”60

Calvin: “Christ was determined to be the Son of God, by openly exerting his truly heavenly power… when he rose from the dead… He was declared by power, because the power peculiar to God shone forth in him, and uncontestably proved him to be God; and this was indeed made evident by his resurrection.”61

Alford: “It is not the objective appointment of Christ as the Son of God, that is spoken of, but the subjective manifestation in men’s minds that He is so: not of Christ’s being what He is, but of the proof of that fact by His Resurrection.”62

Darby: “Resurrection was the public demonstration that He was the Son of God with power, victory over the full wages of sin as seen in this world; but the opened eye would have seen the same power in the exclusion of sin itself in absolute and perfect holiness all His life through.”63

Gaventa: “The resurrection demonstrates something about Jesus rather than that the resurrection brings about a change in Jesus… it implies no change of status or ontology (much less an early form of adoptionism)… the formula has to do with what human beings are able to acknowledge about the gospel, rather than with stages in the development of Jesus Christ.”64

The central claim in all these authors (representing quite a historical spread) is that ὁρίζω means that something always true of Christ, that he is the eternal Son of God, was revealed in resurrection. Think about this position as the exact reverse of the magician’s words: “Now you see it, now you don’t!” Reversed: what we didn’t and perhaps couldn’t see about Jesus, now we see since he has been resurrected to glory.

3. Change in status or function. “Now he does what he formerly didn’t.”

Translations of this sense gravitate towards “appointed” and view these verses as mainly describing a two stage christology. Representative scholars who adopt this view include Cranfield, Dunn, Moo, Schreiner.

Schreiner: “The new dimension was… his heavenly installation as God’s Son by virtue of his Davidic sonship. In other words, the Son reigned with the Father from all eternity, but as a result of his incarnation and atoning work he was appointed to be the Son of God as one who was now both God and man… The idea here, then, is not that Jesus was “declared” or “shown to be” at the resurrection what he was all along, namely, the eternal Son of God. Rather, the point is that Jesus was “appointed” to be God’s Son in power at the resurrection of the dead. He was exalted to a level of power and authority that he did not have previously… The appointment of Jesus being described here is his appointment as the messianic king… Jesus entered a higher rank of sonship upon his resurrection.65

ESV Study Bible: “Jesus was declared by God the Father to be the Son of God in power when he was raised from the dead and installed at God’s right hand as the messianic King. As the eternal Son of God, he has reigned forever with the Father and the Holy Spirit. But this verse refers to Jesus as the God-man reigning in messianic power (“Son of God” was a Jewish title for the Messiah), and this reign began (i.e., was declared or initiated) at a certain point in salvation history, i.e., when Jesus was raised from the dead through the Holy Spirit.”

Dunn: “That status or role is described as ‘Son of God in power’… It indicated that Jesus’ divine sonship had been ‘upgraded’ or ‘enhanced’ by the resurrection, so that he shared more fully in the very power of God, not simply in status (at God’s right hand), but in ‘executive authority,’ able to act on and through people in the way Paul implies elsewhere (e.g., 8:10; 1 Cor 15:45; Gal 2:20; Col 2:6-7). Jesus did not first become God’s Son at the resurrection; but he entered upon a still higher rank of sonship at resurrection. Certainly this has to be designated a “two-stage Christology,” though what precisely is being affirmed of each stage in relation to the other is not clear… That being said, it remains significant that these early formulations and Paul saw in the resurrection of Jesus a “becoming” of Jesus in status and role, not simply a ratification of a status and role already enjoyed on earth or from the beginning of time.”66

It is clear that these scholars take the change to be related to status and role or power and authority. Jesus now reigns as the messianic king. Both Dunn and Schreiner nonetheless affirm that this entails some manner of upgraded, enhanced, or a higher rank of sonship. It is interesting to me that all the verses Dunn then cites to substantiate this interpretation refer to Christ as the indwelling, life-giving Spirit. These verses seem to mean something more or different from mere messianic reign. They point to a transformation of Jesus in resurrection not simply an exaltation.

Witness Lee’s Interpretation

The Recovery Version (following the RSV) opts for the translation “designated.” The translation choice itself has a subtle felicity to it, for definitionally it encompasses the second two senses of horizo that we just looked at: declaration/revelation and appointment.

Affirming Position 2—Following Alford

Lee starts out with the logic of position two above. When the eternal Word of God became flesh “no one could recognize” who he really was. Outwardly, he looked like any old human being, but because he was the Son of God saying and doing the extraordinary, he was a mystery that perplexed people. His go-to example for this is a carnation seed: before it blossoms it is difficult for most people to determine what kind of seed it is; after it blossoms, it is easy to recognize. “Its blossom is its designation.”67 This is Alford et al’s position above.

Affirming Position 1.b—Following Gregory of Nyssa

But it is obvious that Lee is interested in something more than this. In fact, his example works at another level—the blossom of the carnation is the seed in a different form, so Christ’s humanity in resurrection blossoms in another form. Lee’s main interest and emphasis in these verses is not the revelation of the eternal Logos in Jesus since conception, but the transformation of the human nature of Jesus in resurrection. This is position 1.a above, similar to Gaffin, but really following Gregory of Nyssa. Lee is no adoptionist. He has an incarnational, “from above,” high christology. He repeatedly affirms that “before his incarnation, Christ, as a divine Person, already was the Son of God.”68 Lee also affirms Chalcedon—Jesus is one person in two natures, both of which are preserved without confusion in the hypostatic union. But Lee’s interest here is on the status of Christ’s flesh after the resurrection and how this relates to the gospel (remember vv 3-4 are Paul’s opening definition of the content of the gospel). For Christ to be designated the Son of God in resurrection is for Jesus to sanctify, uplift, transform, and deify his humanity.69 The deification of Jesus’ flesh doesn’t happen, in Lee’s mind, until resurrection, although since birth the Logos had assumed flesh. In this sense, Lee can say that “Through this designation the Christ who was already the Son of God before His incarnation became the Son of God in a new way… in a way that is more wonderful than before.”70 Although “Son of God in a new way” will perhaps make some evangelicals or Reformed nervous, it is very similar to the quotes we saw above from Godet, Hengel, Gaffin, and Dunn, all of whom used this kind of language, though with various meanings.

When Lee says he became the Son of God “in a new way” he means at least two things. First, it means “his humanity became divine”71 and his flesh was “transfigured into a glorious substance.”72 These two statements echo almost verbatim Gregory of Nyssa and Origen (above). Lee takes this divinization or “sonizing” of Jesus’ humanity to be the begetting that Psalm 2:7 and Acts 13:33 speak of. Lee takes Son here in its robust ontological import in the economy of God and not as a mere official title of the messianic King. This begetting IS the designating. In this way, Jesus, the Man in the flesh, was begotten and designated the Son of God.

Kerry Robichaux understands Lee to be saying here:

His humanity was also brought into sonship, not merely through a communication of properties but more intrinsically through the germination of the divine life within Him, which is the essence of resurrection. This process of germination in His resurrection, analogous to but not completely identical with the process of germination in natural birth, was a birthing of His humanity into new creation and divine sonship. Now, not only was He the Son of God by virtue of His eternal existence in the Godhead, but He was the Son of God also in His humanity.73

Second, Son of God “in a new way” means that the only begotten Son of God is now the Firstborn Son of God, because in his resurrection he also regenerated all his believers. They too have humanity and divinity, just like him, although their full conformation to his image must still be worked out in time and through their own resurrection.

The Goal of the Gospel

Since Christ is the prototype for what God is producing in all the believers, designation is related to deification and incorporation, and this is the ultimate goal of the gospel (even though justification is its unshakeable base). After going through this interpretation of Romans 1:3-4, Lee says, “This is the mystery that God became man to make man God.”74 And this happens precisely through the two stages that anchor these verses, incarnation and resurrection. In another place after rehearsing this same exegesis, he says, “This matter is basic for understanding that the issue of Christ’s glorification is the incorporation of the consummated God with the regenerated believers.”75 So ultimately, Lee cashes out Romans 1:4 in 8:29-30, where Christ is called the Firstborn among many brothers, all of whom have been predestinated, conformed to the image of God’s Son and glorified like him.

This dovetails with Sanday and Headlam and Joshua Jipp’s view (above) that the meaning of horizo must be found in the fuller context of Paul’s writings, since the immediate location of Romans 1:4 doesn’t say enough. This fuller context is, at minimum, provided by Romans 8.

It is interesting to note that in Romans Paul uses three instances of horizo words:

- Paul was ἀφορίζω (apo + horizo) unto the gospel of God (1:1)

- The gospel concerns God’s Son who was ὁρίζω (horizo) God’s son through resurrection (1:4)

- All Christians were προορίζω (pro + horizo) to be conformed to the image of God’s Son so that he might be the Firstborn among many brothers (8:29-30)

Each instance of horizo in Romans is connected to the gospel or God’s purpose. This should have significant bearing on how we understand what horizo means in relation to Christ in chapter 1.

The placement of this christological statement in the letter, its pre-Pauline confessional status, and its usage to define the content of the gospel all underscore its importance for the letter as a whole, for, if “the content of Paul’s ‘gospel’ is elaborated from 1:16 through 8:39,”76 its content is debuted and defined here (supplementary definitions of the gospel in Romans appear in 1:16; 10:9; and 16:25).

When Paul says that the gospel of God concerns God’s Son, he is making a statement about the content of the gospel. Lee picks up on this and says, “The central message of the book of Romans… the central point of the gospel is not forgiveness of sins. It is the producing of the sons of God… Christ was designated the Son of God, and we also are designated the many sons of God. This is the main point of the gospel.”77 While the word gospel appears 11x in Romans and the letter exhibits an evangelical exuberance, circling the theme like a path around a mountain peak—in his preface to Romans Luther calls it “the purest gospel” and “quite sufficient to illumine the whole Scriptures”78—the base camp and summit flag of the gospel, its anchor points, are Romans 1:3-4 and 8:29-30. As Lee never tired of saying: “Romans 1:3-4 give us Jesus as the prototype. In Romans 8:29-30 we have the many sons as the mass production.”79

Conclusion

Lee had a high view of Romans 1:3-4 and offers a compelling view of how these verses are at the heart of the gospel. He felt that there was much to know about the designation of the Son of God, particularly five things: “There are several points related to Christ’s designation that we need to study and know. For instance, we need to know what Christ was designated to be, what it means to be designated, the way in which He was designated, why He needed to be designated, and the outcome of His designation.”80 In this LONG post, I hope to have shed a little light on what he thought about all this and how it stacks up to other historical positions.

- Lee, Life-Study of Romans, 18, 21. ↩︎

- See Lee, Life-Study of First and Second Samuel, 155; Life-Study of Hebrews, 157. ↩︎

- Lee, Romans, 550. ↩︎

- See Michael Reardon, “The Church is Christ: The Wirkungsgeschichte of Interpretin Pauline Soteriolgoy as Ecclesial Deification,” in Transformed into the Same Image: Constructive Investigations into the Doctrine of Deification (IVP, 2024), 16-37. ↩︎

- Lee, Romans, 560. Douglass Moo agrees: “Here, Paul makes clear, is the heart of the gospel that he will be setting forth in great detail for the Romans,” see Moo, Romans, NICNT, 49. ↩︎

- See Robert Jewett, Romans: A Commentary, Hermeneia, 107. ↩︎

- Lee, Romans, 557, 552. ↩︎

- Matthew W Bates, “A Christology of Incarnation and Enthronement: Romans 1:3-4 as Unified, Nonadoptionist, and Nonconciliatory,” The Catholic Biblical Quarterly 77.1 (2015): 108. ↩︎

- Beverly Gaventa is a contemporary scholar who demurs; see Gaventa, Romans, The New Testament Library, 13: “Instead of drawing on and perhaps modifying an earlier creedal formulation, Paul appears to be crafting a definition of the gospel, incorporating some expressions he anticipates will be familiar to the Roman congregations, and anticipating explication of the summary in vv. 16-17 and much more elaborately in the body of the letter to follow.” ↩︎

- Jewett, Romans, 98. ↩︎

- Both Nee and Lee recognized that the NT contained pre-Pauline hymns, confessions, and liturgical tidbits. Nee calls these creedal snippets “choruses;” see CWWN 54:125-26. ↩︎

- Jewett, Romans, 97. ↩︎

- Martin Hengel, Son of God: The Origin of Christology and the History of Jewish-hellenistic Religion, 60. ↩︎

- Ernst Käsemann, Commentary on Romans, 11. ↩︎

- Gaventa, Romans, ad loc. ↩︎

- Lee, CWWL 1994–1997, vol. 2, 60. ↩︎

- Lee, CWWL 1994-1997, vol 1, 217. ↩︎

- Lee, CWWL 1994-1997, vol 5, 333. ↩︎

- Lee, CWWL 1994–1997, vol. 2, 149. ↩︎

- Hengel, Son of God, 59. ↩︎

- Lee, CWWL 1994-1997, vol 1, 216. ↩︎

- Lee, CWWL 1994-1997, vol 1, 390. ↩︎

- Origen, Comm. in ep. ad Rom. 1.6.2, trans. Thomas P. Scheck, Origen: Commentary on the Epistle to the Romans Books 1-5 (Washington, D.C.: Catholic University of America Press, 2001), 73. ↩︎

- Jewett, Romans, 108. ↩︎

- Jewett, Romans, 104. Matthew Bates closely engages Jewett’s argument and disagrees. ↩︎

- Lee, CWWL 1984, vol. 2, 240. ↩︎

- Sanday and Headlam, Romans, ICC, 7. ↩︎

- Joshua Jipp, “Ancient, Modern, and Future Interpretations of Romans 1:3–4: Reception History and Biblical Interpretation” in Journal of Theological Interpretation 3 (2009): 257. ↩︎

- Jipp, “Interpretations of Romans 1:3–4,” 255. ↩︎

- Frederick Godet, Commentary on St. Paul’s Epistle to the Romans, 78-79. ↩︎

- Hengel, Son of God, 60. ↩︎

- Nee took Godet to be “a highly respected and spiritual Swiss theologian” and “an orthodox theologian… a very spiritual man;” see, Nee, CWWN, vol. 62, 297, 302. Lee participated with Nee in this Bible study training where they used Godet. Lee later referred to some of Godet’s insights as “marvelous,” in Life-study of Colossians, 378. ↩︎

- Godet, Romans, 76-77. ↩︎

- Lee, Romans, 20. ↩︎

- At times he simply equates designation with glorification, e.g., Lee, Romans, 551. ↩︎

- Gérard Genette, Narrative Discourse: An Essay in Method, trans. Jane E. Lewin (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1980), 30. Online. ↩︎

- Gregory of Nyssa, Catechetical Discourse 11. ↩︎

- See Jipp, “Interpretations of Romans 1:3–4,” 246: “It is necessary to emphasize the ubiquity with which Acts 2:36 is invoked as an interpretive key in modern interpretations of Rom 1:4.26.” ↩︎

- Rudolf Bultmann, Theology of the New Testament, 1:50. ↩︎

- See pp. 218–25, 226, 294. For helpful reviews of Ehrman’s book and an evangelical response, see “Who Do You Say That I Am?,” in Affirmation & Critique 14.2 (Fall 2014): 67-98. Online. ↩︎

- Moo, Romans, 46. ↩︎

- Richard Gaffin, The Centrality of the Resurrection, 11. See this review at Themelios for more. ↩︎

- John Behr, The Nicene Faith, II/2, 436. ↩︎

- Coakley, The Broken Body, 54. ↩︎

- Origen, Comm. in ep. ad Rom. 1.6.1; Scheck, p. 73. ↩︎

- Origen, Cels 3.41. ↩︎

- Origen, Comm. in Joann. xxxii.25. ↩︎

- See Comm. in ep. ad Rom. 1.5.5: “Undoubtedly, he became that which previously was not, according to the flesh. According to the Spirit, however, he existed first, and there was never a time when he was not.” ↩︎

- Origen, Cels 3.41. ↩︎

- For relevant quotes and commentary, see Behr, Nicene Faith, 445-51. ↩︎

- For relevant quotes and commentary, see Behr, Nicene Faith, 436-45. ↩︎

- For relevant quotes and commentary, see Behr, Nicene Faith, 451-58. ↩︎

- Sarah Coakley, ‘Mingling’ in Gregory of Nyssa’s Christology: A Reconsideration,” in The Broken Body: Israel, Christ and Fragmentation (2024), 54. ↩︎

- Coakley, The Broken Body, 56. ↩︎

- Theoph. (GNO III.1:126-127). ↩︎

- C.Eun. 3.3.44. ↩︎

- C.Eun. 3.3.62 ↩︎

- Behr, The Nicene Faith, II/1, 235 ↩︎

- Ambrosiaster, Commentary on Paul’s Epistles, CSEL 81.1:16. ↩︎

- Theodoret of Cyrus, INTERPRETATION OF THE LETTER TO THE ROMANS. 103IER, Migne PG 82 col. 52. Quoted in Ancient Commentary, p. 11. ↩︎

- Calvin, Commentary on Romans, ad loc. ↩︎

- Alford, NT For English Readers, Vol 2, Part 1, p. 3. ↩︎

- John Nelson Darby, “Exposition of the Epistle to the Romans,” Collected Writings of J.N. Darby: Expository 5. ↩︎

- Gaventa, Romans, 14. ↩︎

- Schreiner, Romans (1998), 39, 42. ↩︎

- James DG Dunn, Romans 1-8, WBC 38A, (1988), 14. ↩︎

- Lee, Romans, 19; see also, 550-51. ↩︎

- Lee, Romans, 19. ↩︎

- Lee, Romans, 19. For this as the deification of his humanity, see Life-study of Job, 165. ↩︎

- Lee, Romans, 558, 560. ↩︎

- Lee, CWWL 1994–1997, vol. 2, 147. ↩︎

- Lee, Romans, 560. ↩︎

- Kerry Robichaux, “Christ the Firstborn.” Affirmation & Critique, 2.2 (April 1997): 37. ↩︎

- Lee, CWWL 1994-1997, vol 1, 4. ↩︎

- Lee, CWWL 1994-1997, vol. 5, 333. ↩︎

- Jewett, Romans, 97. ↩︎

- Lee, Life-Study of Romans, 544-45. ↩︎

- Luther, LW 35:366-67. ↩︎

- Lee, Romans, 22. ↩︎

- Lee, CWWL 1994–1997, vol. 2, 146. ↩︎