Although all humans share the creative use of language, it seems that not all of us are using it. Especially in today’s social-media saturated world, where the ephemeral nature of conversation is touted, the art of writing well or of producing something to be read at length is vanishing. This is most alarming to writers, but also to the rest of us who still want to communicate beyond chat boxes, text messages, or the 140 characters of a tweet.

Many people don’t actually read anymore, they scan. The difference is whether or not you are actively processing information and emotionally responding to it or whether you’re just getting an eye exercise out of the event.

In writing a blog you want to find some means to engage your reader. And if you are blogging about what really matters this is all the more important. Style, rhythm, vocabulary, syntax, metaphor are all part of the linguistic devices that can accomplish this. The goal is not to merely communicate information. This could be done more efficiently through bulleted lists, and it certainly would demand less of the reader. But there is something to the creative manipulation of words that is worth our effort.

Christ Himself in His eternal preexistence is the Logos or Word. The written Word of God came to us authored by God as a book, not as a neatly packaged creed or a logically ordered outline. Even truths such as justification or the nature of God are not collected altogether for our convenience. No book of the Bible is entitled, On Knowing God or The Basics of Salvation. The divine truths are scattered and hidden throughout all 66 books of the Bible like the pieces of a jigsaw puzzle, “here a little, there a little (Isaiah 28:10).”

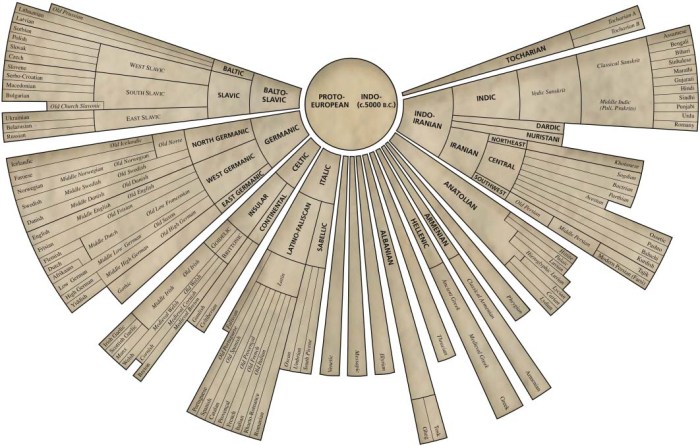

Even the two original languages, Hebrew and Greek, that were employed to pen the Scriptures seem ordained by God.

The Old Testament is a figurative portrait of God’s eternal economy and the Hebrew language is perfectly suited to accomplish this. Hebrew is a pictorial language in which events are not merely described but verbally painted. It is vivid, concise, and simple and relies more on observation than reflection. With Psalm 23:1, English requires 9 words to translate the 4 Hebrew words. The entire chapter in Hebrew only contains 55 words, where as most English versions need 113.

The New Testaments is the practical fulfillment of God’s eternal economy as the caption under the picture, describing the reality, in Christ, of what was typified in the Old Testament, and Greek again fits the bill. The distinguishing characteristics of the Greek language are its strength, clarity, and richness. It is well suited for the doctrinal precision that elucidates the divine realities. For example, the definite article alone can inflect 24 different ways according to gender, number, and case. The result is loaded sentences that are tagged with lots of information to clarify what is being modified, referred to, who is doing the action, etc. Not much is left to guess work.

A great example is Ephesians 6:17,

And receive the helmet of salvation and the sword of the Spirit, which is the word of God.

Most people think the word of God here refers back to the sword, aka that the word of God is the sword. And people casually refer to the Bible as their sword, “Don’t come to church without your sword.” However, the Greek makes it clear that the relative pronoun ‘which’ refers to the Spirit. This means that the Spirit is the word of God! This understanding opens a whole vista of revelation. Thanks to Greek, this is possible.

If God took great care to communicate His eternal purpose to humanity through human language, we should at least strive for the same in ministering the word. I’m not advocating rigid, stuffy formalism or technical jargon. Just a healthy dose of encouragement to practice developing our skill to convey God’s word whether through conversation or blogging.

Kevin DeYoung had a great article recently on writing well for those blogging about the divine truths. Here’s a preview:

All of us appreciate good writing. We may not know that, and if we know that we probably don’t know why. But we all prefer to read something written well. There’s a way to communicate the truth and have it sound muddled. There’s a way to make it understandable. And then there’s a way to make it sing. That’s the difference between clear prose and great prose.

Pingback: Les Misérables and Spiritual Portraits « life and building

Pingback: Why Reading Books is Important & My 2014 List | life and building

Thanks for the article. I do have to say, however, that you rely on ideas about Hebrew and Greek which were discredited long ago. Eg – “[Hebrew] is vivid, concise, and simple and relies more on observation than reflection”; “The distinguishing characteristics of the Greek language are its strength, clarity, and richness. It is well suited for the doctrinal precision that elucidates the divine realities.” This is simply not so, as people who study the languages can attest.

The example you give, “sword of the Spirit”, is as ambiguous in Greek with its genitive case as it is in English. In both languages it may mean the sword “which is the Spirit/spirit”, “given by the Spirit”, “characterized by the Spirit/spirit”, “sword that belongs to the Spirit”, the “sword made out of Spirit/spirit”. What determines meaning is context and general conventional usage of the language in other biblical contexts.

We know that Hebrew and Greek were languages ordained by God to communicate his word, because that’s what we have in our hands. And what of Aramaic, the third language he selected – if Hebrew was the perfect medium, why did God switch to Aramaic in Ezra and Daniel? And isn’t it so that an All-Mighty God could communicate his word in English or in whatever language he selected?

LikeLike

Hi Gary,

Can you please direct me to some resources on your understanding that the view I present here of the original languages has been discredited? In this post I’m relying on a chapter entitled, “Biblical Languages” by Dr Larry L Walker in The Origin of the Bible. Walker was professor of Old Testament and Semitic Languages at Mid-America Baptist Theological Seminary and served on the translation committee for the NIV.

The point of the Eph 6:17 was not to imply that there are no ambiguities in Greek, but to show that the Spirit is linked to the word of a God. This connection is clearer in Greek than it is in most English translations.

The bigger question is not can God communicate in any language, but why would God switch the mode of revelation from direct, spoken communication to a once for all written text? This brings in questions of ascertaining meaning at three levels 1) authorial intent 2) reader communities and 3) applied external moralities. For a great response to this question I highly recommend the following article,

Click to access 99_03_a1.pdf

Also, I think Augustine has a lot of insight on this issue in book 12 of his Confessions, particularly, his view that the biblical authors “use a small measure of words to pour out a spate of clear truth” (12.27.37).

LikeLike